Abstract

Suture-mediated vascular closure devices (SMVCD) can be applied to close non-vascular structures, although this represents an off-label use. A 53-year-old woman who underwent hysterectomy and chemoradiation therapy due to endometrioid adenocarcinoma two years ago presented for generalized peritonitis due to anastomotic perforation following adhesiolysis and resection. CT revealed multifocal peritoneal abscesses. During perigastric fluid drainage, a pigtail drainage catheter was inadvertently placed into the stomach. To reduce the risk of gastroperitoneal fistula and peritonitis, the gastrostomy site was percutaneously closed using an SMVCD. Immediately after closure, gastrography using orally administered contrast medium and a 10-month follow-up CT demonstrated no leakage or procedure-related complications. This case suggests the potential for safe off-label use of vascular closure devices in the closure of gastrointestinal tract punctures.

-

Keywords: Vascular closure device; Gastrostomy; Perclose; Percutaneous drainage; Case report

Introduction

Percutaneous drainage (PCD) catheters may occasionally be misplaced during placement for intraperitoneal fluid collections, although such occurrences are rarely reported. Typically, large-bore catheters (> 8 French) are used, standard treatment of gastrointestinal catheter malposition includes either surgical primary closure or catheter removal after long-term indwelling of the catheter under fasting to allow tract maturation. On the other hand, some investigators insisted that catheters can be removed from the stomach without any special measures up to 14 French if fasting is maintained [

1]. However, in cases where tract maturation is delayed, such as malnutrition, old age, cancer, chemotherapy, or steroid use, tract closure may be difficult. Several investigators have reported successful gastrostomy repair in swine models using suture-mediated vascular closing devices (SMVCD; Perclose ProStyle, Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA). While the safety and efficacy of SMVCD in vascular closure are well established [

2,

3], evidence for non-vascular indications was scarce. Here, we report the successful closure of a misplaced gastric PCD tract using an SMVCD.

Case Report

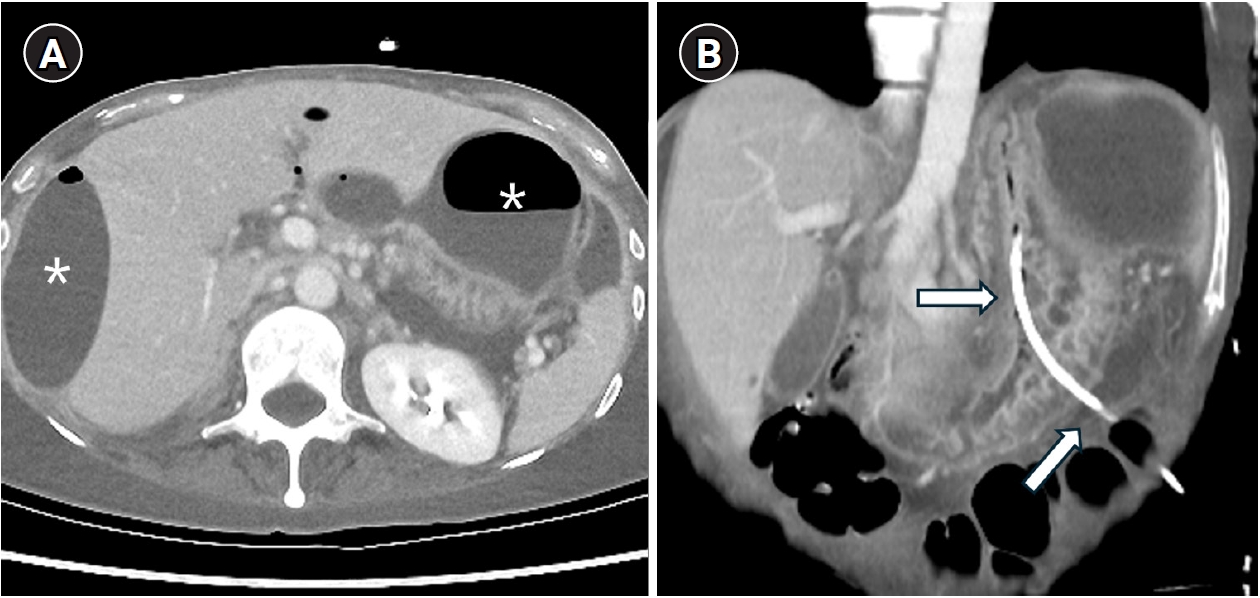

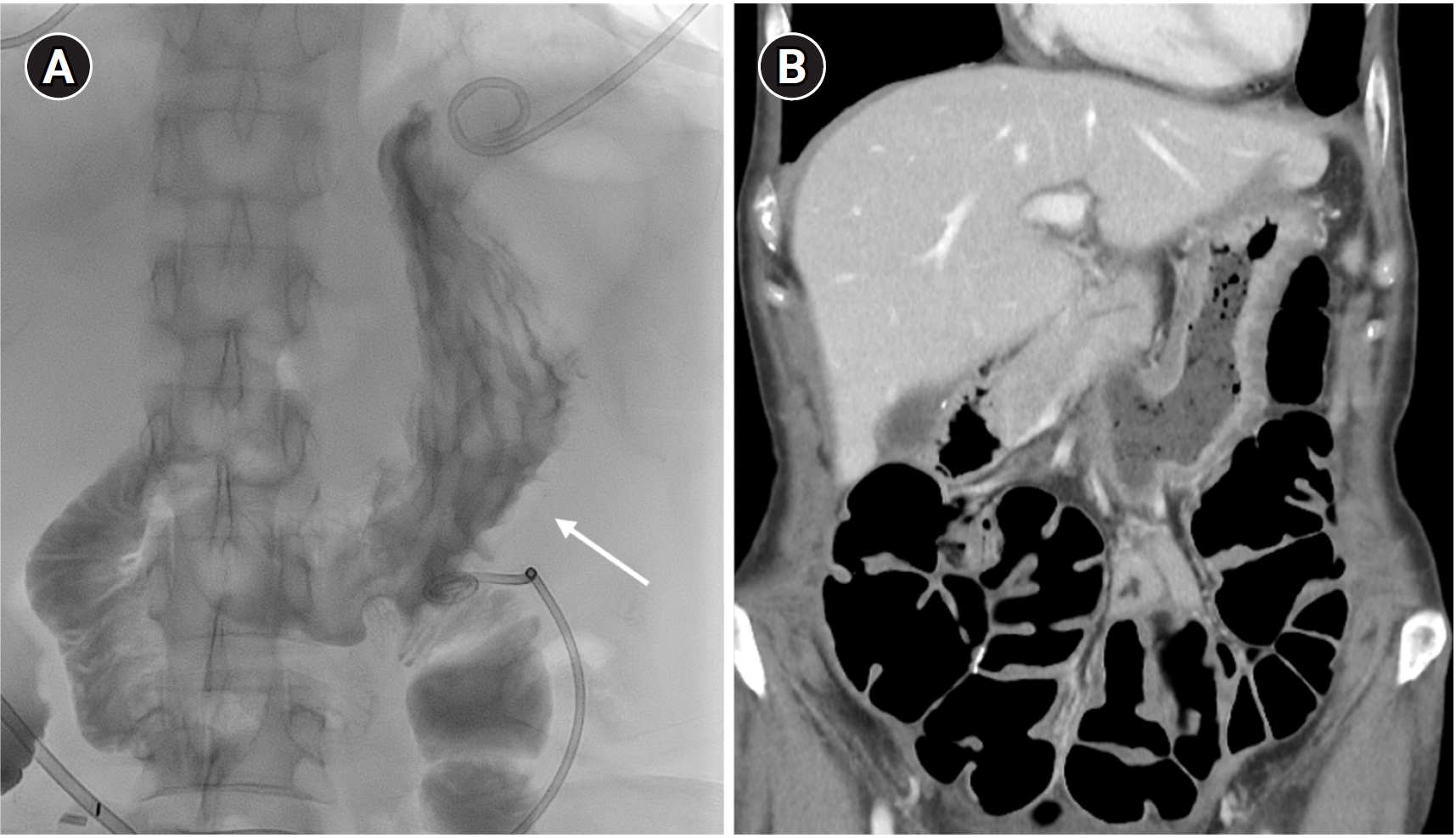

A 53-year-old woman with a history of total abdominal hysterectomy for endometrioid adenocarcinoma 2 years earlier and subsequent adjuvant chemoradiation therapy presented with adhesive ileus. She underwent adhesiolysis and small bowel resection; however, the surgery was complicated by anastomotic leakage, resulting in the formation of multifocal intraperitoneal abscesses. The perigastric abscess (

Fig. 1A) was accessed under ultrasonographic and fluoroscopic guidance. The following day, CT showed an 8.5-French PCD catheter located within the stomach (

Fig. 1B).

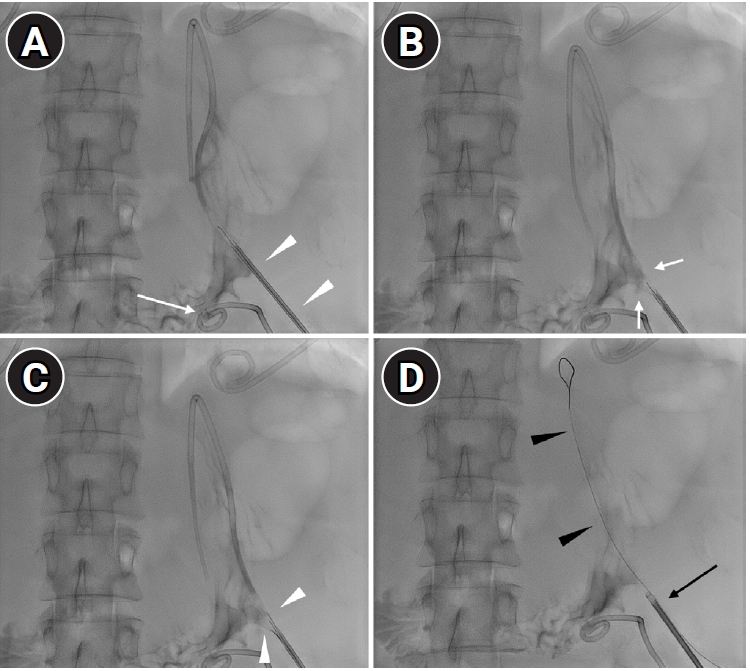

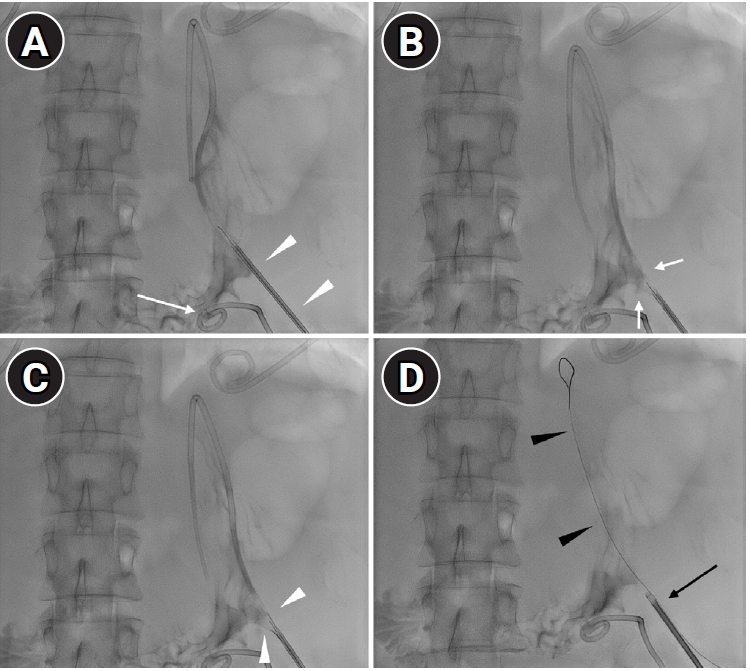

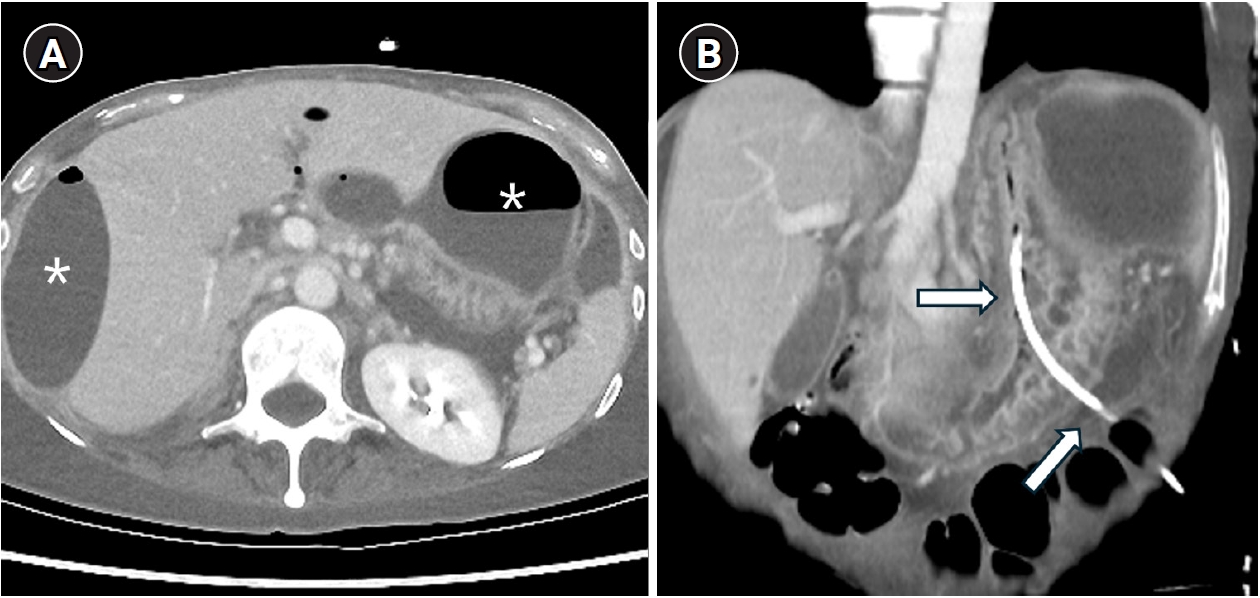

The cause of malposition was not clear, however, it may have been related to inadvertent advancement of the micropuncture needle or misinterpretation of ultrasonographic findings between the gas-filled stomach and the abscess. A wide space between the stomach and peritoneal wall, along with malnutrition due to prolonged fasting, may hinder normal tract maturation. In addition, instability caused by peristalsis and the lack of an anchoring system–unlike feeding gastrostomy–may further delay tract formation, necessitating safe closure of the perforation. After multidisciplinary discussion, safe retrieval of the PCD catheter was planned using a SMVCD instead of surgical treatment, as the patient had severe radiation-associated fibrosis from prior oncologic treatment. The catheter was exchanged over a 0.035-inch guidewire, and the SMVCD was advanced along the wire (

Fig. 2A). The foot was deployed and slightly retracted to achieve secure attachment under fluoroscopic guidance (

Fig. 2B). The needles pierced through the gastric wall by pushing the plunger and were then retracted (

Fig. 2C), and the puncture site was cinched using the suture trimmer (

Fig. 2D).

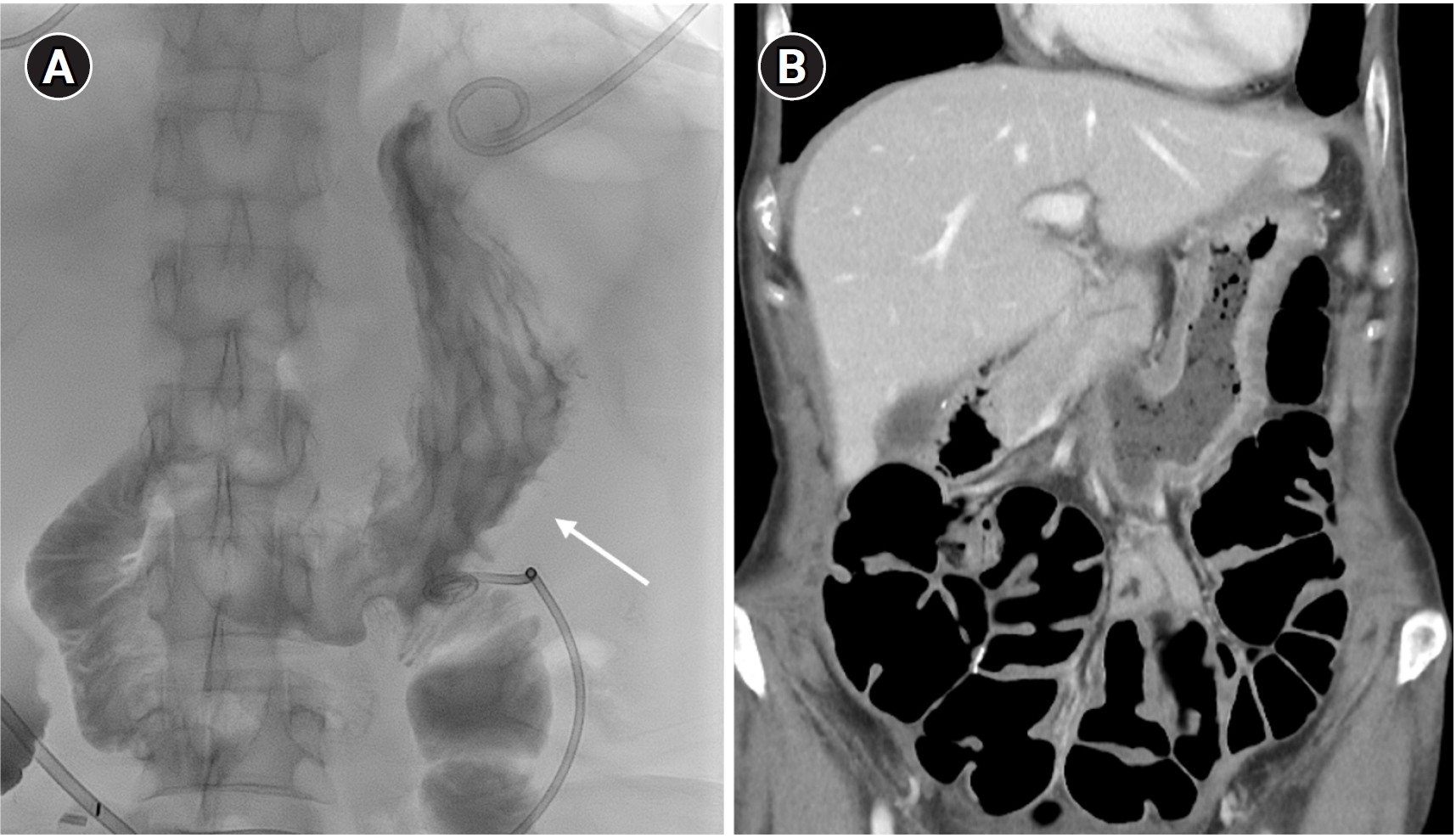

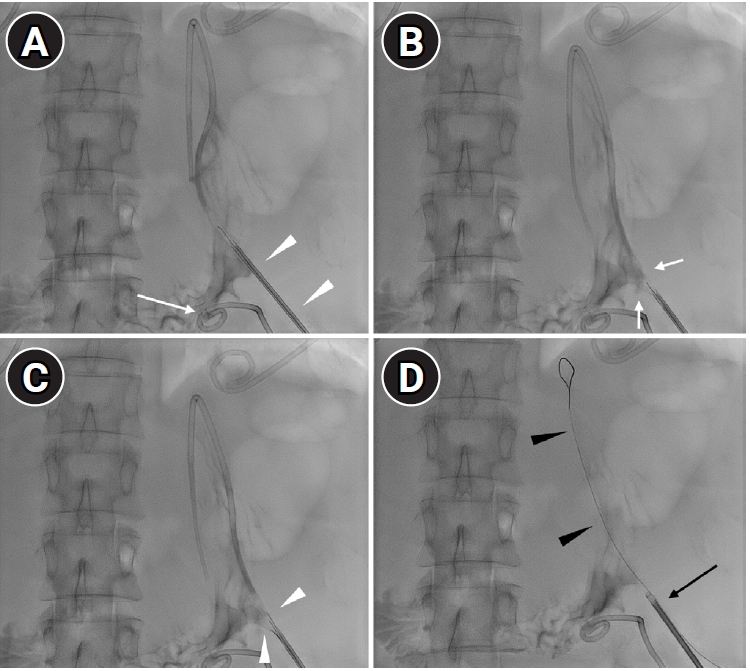

Post-closure gastrography with water-soluble contrast medium demonstrated no leakage at the puncture site (

Fig. 3A). To ensure the safety of closure site and to manage ongoing jejunal leakage, the patient was kept fasting for 6 days before starting a soft diet. The patient subsequently underwent an additional small bowel resection for refractory bowel leakage. Clinical follow-up and CT after 10 months showed no procedure-related adverse events (

Fig. 3B).

Discussion

SMVCDs are primarily indicated for the percutaneous delivery of suture for artery or vein to reduce time to hemostasis. Although not as urgent as vascular hemostasis, visceral organ perforations also require secure closure to prevent generalized peritonitis or abscess formation. Conventional percutaneous procedures such as feeding gastrostomy or jejunostomy prevent leakage using fibrosis along the track by long-standing foreign body reaction. However, tract maturation requires a considerable amount of time, and urgent cases often necessitate surgical intervention. The present case demonstrates the potential of SMVCDs to safely repair hollow visceral organ perforations as a less invasive alternative to surgery.

Several investigators have reported the feasibility of using SMVCDs for gastrostomy closure. Cho et al. reported successful closure of gastrostomies in a swine model using a preclosure technique, with no significant adverse events, suggesting the potential clinical applicability of SMVCDs for this indication [

4]. In their study, the intraluminal position of the foot was confirmed by injecting a contrast agent via the marker lumen, similar to the technique used in arterial closure. Jung et al. also demonstrated that the use of single or double SMVCDs was feasible and safe for gastrostomy closure in a swine model [

5]. Similarly, Shlomovitz et al. reported successful SMVCD-assisted closure of gastrostomies created for duodenal stent placement in a porcine model [

6]. In contrast, Mueller et al. reported 11 cases of safe removal of misplaced catheter during abdominal drainage with no additional procedure; however, the catheters had been left in place for an average of 17 days [

1]. Surgical repair may provide a straightforward treatment option for misplaced catheters. Several reports have also described misplaced cystostomy catheters in the gastrointestinal tract that were successfully treated with laparoscopic repair [

7,

8]. Our case provides additional evidence supporting the safe application of SMVCDs for gastrostomy closure under fluoroscopic guidance.

Several considerations are necessary before the use of SMVCDs in non-vascular organs. First, although they may be applicable to organs such as the small and large intestine, urinary bladder, and gallbladder, device limitations must be considered. The sheath length restricts feasibility in the urinary bladder and gallbladder unless the distal sheath is shortened. Secondly, the target organ should be located within approximately 6 cm of the skin to accommodate the guide tube length; deeply located puncture sites are less suitable. Furthermore, the mobility of the small intestine may hinder accurate deployment. Thirdly, unlike in blood vessels, no blood regurgitates through the proximal marker. Proper positioning can be confirmed by fluoroscopic imaging or injection of a contrast agent through proximal marker lumen. In addition, the success of closure could be verified by fluoroscopic imaging using a contrast medium. Fourthly, current recommendations for vascular applications limit use to arteries < 21 French and veins < 24 French, however, no guidelines exist for visceral organs [

2]. Further clinical studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of SMVCDs for gastrointestinal applications.

This report describes a single case, and therefore, generalizability is limited. Broader clinical experience is required to establish the safety and efficacy of SMVCDs in non-vascular applications.

Conflict of interest

Dong Jae Shim has been the Deputy Editor of Korean Journal of Interventional Radiology. However, He was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contributions

All the work was done by Dong Jae Shim.

Fig. 1.A 53-year-old woman with a history of adhesiolysis for ileus presented with fever and abdominal pain. (A) Axial CT image shows multiloculated intraperitoneal fluid collections requiring drainage (asterisks). (B) Coronal CT image shows a percutaneous drainage catheter inadvertently placed within the stomach (arrows).

Fig. 2.Closing procedure. (A) An additional catheter was placed for perigastric fluid drainage (arrow). The misplaced drainage catheter was exchanged over 0.035-inch guidewire, and a suture-mediated vascular closing device was advanced along the guidewire (arrowheads). (B) The device foot was deployed and slightly retracted to create tenting of the gastric wall (arrows). Because the foot is radiolucent, proper placement was confirmed by gastric wall configuration. (C) The needles (arrowheads) penetrated the gastric wall upon pushing the plunger. (D) The suture was cinched using the trimmer (black arrow). A 0.018-inch guidewire (black arrowheads) was placed before removal of the SMVCD to allow a second attempt in case of failure.

Fig. 3.Follow-up. (A) Immediate post-procedural gastrography with oral contrast medium shows no leakage at the puncture site (arrow) and no structural deformity. (B) Ten-month follow-up CT shows no leakage or deformity of the stomach.

References

- 1. Mueller PR, Ferrucci JT, Butch RJ, Simeone JF, Wittenberg J. Inadvertent percutaneous catheter gastroenterostomy during abscess drainage: significance and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:387-391.

- 2. Apostolos A, Konstantinou K, Ktenopoulos N, Panoulas V. Plug- versus sutured-based vascular closure devices for large bore arterial access: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Cardiol. 2025;252:56-66.

- 3. Rylski B, Berkarda Z, Beyersdorf F, Kondov S, Czerny M, Majcherek J, et al. Efficacy and safety of percutaneous access via large-bore sheaths (22-26f diameter) in endovascular therapy. J Endovasc Ther. 2024;31:1173-1179.

- 4. Cho SB, Kim HR, Jung EC, Chung HH, Lee SH, Park BJ, et al. The application of a vascular closure device for closing a gastrostomy opening used for procedural access. Br J Radiol. 2019;92:20180837.

- 5. Jung E, Cho SB, Kim HR, Kim YH, Chung HH, Lee SH, et al. Percutaneous closure of gastrostomy using a suture-mediated vascular closure device in a swine model. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2020;43:781-786.

- 6. Shlomovitz E, Patel NR, Diana M, Pescarus R, Swanström LL. Percutaneous transgastric duodenal stenting and gastrostomy repair using a vascular closure device: proof of concept in a porcine model. Surg Innov. 2022;29:139-144.

- 7. Rajmohan R, Aguilar-Davidov B, Tokas T, Rassweiler J, Gözen AS. Iatrogenic direct rectal injury: an unusual complication during suprapubic cystostomy (SPC) insertion and its laparoscopic management. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2013;85:101-103.

- 8. Wu CC, Su CT, Lin AC. Terminal ileum perforation from a misplaced percutaneous suprapubic cystostomy. Eur J Emerg Med. 2007;14:92-93.

Citations

Citations to this article as recorded by